Thomas Lister (1810 –

1888)

Notes on the Barnsley

postmaster and poet

who was a friend of

Ebenezer Elliott, the Corn Law Rhymer

Born at Old

Mill Wharf, near Barnsley, on 11th February 1810, Thomas Lister was

the youngest

of fourteen

children. He was educated at the Quaker Friends' School,

Ackworth, between 1821 and

1824 where he is said to have received a good English education.

He was admired for his athletic feats and physical courage.

After leaving school he worked for

his father, a Quaker gardener and small

farmer, for several years enjoying a rustic and healthy

lifestyle. After Lister

helped Lord Morpeth (later Earl Carlisle) in his election campaign for

the old West Riding of Yorkshire, Lord Morpeth offered him in 1832 the

position of Postmaster at Barnsley,

but as

a Quaker he could not take the oath that was required, so the offer was

withdrawn. Politically,

Lister was hardly a firebrand but he was interested in education,

particularly the education of the working man through the mechanics'

institutes.

In 1839 he

was again offered the position of postmaster at Barnsley, which he

accepted;

the oath having been replaced with a simple form of declaration.

He

retained this position until 1870 when he retired with a pension.

He was

presented with a handsome testimonial at a large public meeting,

presided over

by the mayor of Barnsley.

In 1840, there was a great occasion in London for progressive Quakers. The Friends organised the World Anti-Slavery Convention with 409 delegates attending including thirty or so people who actually came over from the USA. Lister attended the London convention and met two American quakers who are of interest to us. Henry Brewster Stanton (1805-1887) was a Quaker lawyer, activist, journalist and politician who visited the Convention and who travelled round the country meeting fellow Quakers. Stanton had just married a fellow Quaker who like her husband was a staunch abolitionist. The couple had their honeymoon in London and both attended the Convention. Stanton was a great admirer of Ebenezer Elliott and took the opportunity to visit him in his Sheffield workshop in 1840. The other delegate of interest was the anti-slavery campaigner, John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-1892). He was yet another Quaker poet - and a famous one at that! We can assume that Lister met Whittier at the convention through their common interest in the Corn Law Rhymer. (We can also assume that Lister met Stanton at the convention). Whittier was a huge admirer of the Corn Law Rhymer and wrote a poem about him after Elliott died. (It seems a missed opportunity for Whittier not to meet Elliott). Whittier and Lister did meet again later on in life in the States.

In 1841 the 31 year old Thomas married Hannah Schofield (1812-1882) but no children blessed the marriage.

In 1884, aged 74, Lister

visited Montreal & the main Canadian & American cities.

Lister was very elderly to be thinking of sailing to the States,

so he had to be both brave & physically fit to consider it.

(Lister's three brothers had

emigrated to America in 1829/30 and then

moved on to Canada. Lister was probably catching up on nephews, neices

and their parents). The poem "The Home-expelled Britons" is thought to

be one of the first written by Lister and relates to the

emigration of his brothers. When Lister

visited the States, he is known to have called on John Greenleaf

Whittier, the Quaker poet and journalist who was an anti-slavery

campaigner. In a letter by Whittier dated June 1881, he mentioned

that he had had a visit from Lister in the autumn of 1880. (Note the

discrepancies in dates here: 1884 and 1880. Or could Lister have visited the States

twice? He certainly was fond of travelling as we have already

seen.)

Thomas Lister was both poet and naturalist and contributed many articles on birds & weather to the Barnsley Chronicle. He was for a long time President of the Barnsley Naturalists’ Society. Gave many papers to the British Association.

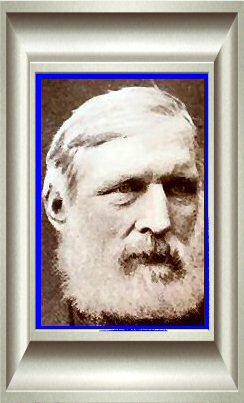

Thomas Lister

1810 - 1888

A very amusing desciption of Lister appeared in a letter by Elliott to GeorgeTweddell. This was 25th February 1845. Tweddell was both poet and historian. The Corn Law Rhymer described his friend as: "You will find him in many respects remarkable - a courageous, energetic, gristle-bodied man, with a bump of "I'll have my own way," bigger than a hen's egg, on his summit ridge; his face is handsome, except the eyes, or rather their position, which is cavernous; the eyes themselves are keen and characteristic; his lips are beautiful. If there is truth in phrenology, his observant faculties should be strong and active, as his writings seem to prove."

Some poems by Thomas Lister

1834 “The Rustic

Wreath”

1837

“Temperance Rhymes”

1838 "Sunset Musings In Milan"

1862 “Rhymes of Progress”

"These Soulless Tools Of Tyranny" (date unknown?)

"Knowledge is Power" (see below)

"The

First Found Flower" (see below)

The

collection of poems called "The Rustic Wreath" was dedicated to Lord

Morpeth. There was a pre-publication list of 1,000 subscribers

including noted people such as the Archbishop of Canterbury, members of

the nobility and members of parliament. (Subscribers were always

wealthy people, and there was always a social gain in seeing one's name

listed next to a high powered celebrity). The first

printing sold 3,000 copies, so Lister was well regarded as a poet. The

book is still available off the

Internet.

|

Knowledge Is Power A poem by Thomas Lister

|

Knowledge

is power, have sages said,

|

He who

inspired the breath

of life |

| The First Found Flower A poem by Thomas Lister |

|

To thee! though not the first of spring's young race, The earliest wild flower, greeting yet mine eye; Ev'n ere the crocus bursts its golden dye, Or primrose pale unveils its modest face - To thee small celandine I yield first place. For thou dost greet me, earliest of the band, That comes as sweetness, after storms and cares. Remembrance of past pleasures! moments bland, Pledge of rich joys, the coming season bears! Well might thy starry cup of golden bloom - Thy lowly virtues - one pure mind awake Who sought, before the art-emblazon'd dome, The flower-crown'd mountain, and the reedy lake - Thee! hallow'd Wordsworth sang - I love thee for his sake. |

TO

THOMAS LISTER ....

Ebenezer

Elliott wrote two poems about the postmaster of Barnsley. Both poems

were called "To Thomas Lister" and are undated, though clearly they

would have been written late in Elliott's life. Neither are outstanding

but they are included here out of interest. Lister would no doubt have

been very pleased to receive the poems from his famous friend.

|

To

Thomas Lister

A Poem by Ebenezer Elliott |

|

Bard

of the Future! As the morning glows, O’er

lessening shadows, shine thou in this land. Till

the rich drone pays Labour what he owes, “Strive

unto death” against his plundering hand; And

bid the temple of free conscience stand Roof’d

by the sky, for ever. “As the rose, Growing

beside the streamlet of the field,” Send

sweetness forth on every breeze that blows; Bloom

like the woodbines where the linnets build; Be

to the mourner as the clouds, that shield, With

wings of meeken’d flame, the summer flower; Still,

in thy season, beautifully yield The

seeds of beauty; sow eternal power; And

wed eternal truth! though suffering be her

dower. Don

whispers audibly; but Wharncliffe’s dread, Like

speechless adoration, hymns the Lord; While,

smiting his broad lyre, with thunder stored, He

makes the clouds his harp-strings. Gloom is spread O’er

Midhope, gloom o’er Tankersley, with red Streak’d;

and noon’s midnight silence doth afford Deep

meanings, like the preaching of the Word To

dying men. Then, let thy heart be fed With

honest thoughts! and be it made a lyre, That

God may wake its soul of living fire, And

listen to the music. O do thou, Minstrel

serene! to useful aims aspire! And,

scorning idle men and low desire, Look

on our Father’s face with meek submitted brow. Yes,

Lister! bear to him who toils and sighs The

primrose and the daisy, in thy rhyme; Bring

to his workshop odorous mint and thyme; Shine

like the stars on graves, and say, Arise, Seed

sown in sorrow! that our Father’s eyes May

see “the bright consummate flower” of mind; Sing

in all homes the anthem of the wise: “Freedom

is peace! Knowledge is Liberty! Truth

is religion." O canst thou refuse To

emulate the glory of the sun, That

feedeth ocean from the earth-fed sky; And

to the storm, and to the rain-cloud’s hues, Saith,

“All that God commandeth shall be done!” |

In the above poem, Elliott encouraged Lister referring to him as "Bard of the Future" and "Minstrel serene." This was something that Elliott was noted for: making positive remarks about upcoming poets, whether or not they displayed any talent. Another thing that we often note with Elliott is the use of local names: here we see the River Don, Midhope Moor, Wharncliffe Side and Tankersley. And we always expect to see religious references (last line) and political comment (lines 3 and 4 for instance).

| To

Thomas Lister A Poem by Ebenezer Elliot |

FRIEND, I

return your English Hexameters, thanking you for

them. More than

forty years since, I constructed such verses, Choosing a

lofty theme, too often worded unsimply. Even now, I

remember one stol’n line of the anthem: “Thou for

ever and ever, God, Omnipotent, reignest!” Though my

verbiage pleased me, long ago did it journey Whither dead

things tend. For Homer’s world-famous metre Cannot in

English be pleasing. Saxon may write it in Saxon, Oft for

dactyl and spondee using iambic and trochee, Pleased –

and making a boast of his wasted labour and lost

time; But with

grace and simplicity none can write it in our

tongue, Though the

sturdy gothic oft runs into it promptly, As it

grandly does in these fine lines from the Bible: “How art

thou fall'n from heav’n, oh, Lucifer, son of the

Morn!” and “Why do the

heathen rage, and the people imagine a vain

thing?” Not unpleasing always, mostly ‘tis feeble, yet stilted, Wanting, in wanting ease, the might which is mightiest, beauty |

Yet can it finely paint the beauty of

form and of colour; Skies, and the sea; or mountains

cloud-like in distance, and

stealing Azure from heav’n; or the daisy fresh

in the dew-gleam of

dawn; or Young June’s blush-tinted hawthorn,

that scatters the snow

of its dropped flowers Over the faded cowslip, and roses

embraced by the woodbine, Under the mute, or songful, or

thunder-whispering forest; But from man’s heart seldom it brings

the tear, which the

angels, Knowing not sorrow, might almost in

their blessedness envy. Slow or rapid, sweet or solemn, in

Greek and in Latin, It is in English undignified, loose,

and worse than the

worst prose. One advantage it has – it must be

utter’d as prose is; And as it may be wanted, if only as

changes are wanted, I subjoin the rule for its fitting or

modern construction: Every line must consist of six feet,

dactyls and spondees, Dactyls and trochees, or dactyls and

both: A dactyl the

fifth foot Must be; a spondee or trochee the

sixth: Each line must

contain not More than sixteen syllables, and not

fewer than thirteen. |

Note, too, the fine image of the red hawthorn shedding its blossom, showing Elliott's love of nature. In his destitute years, Elliott distracted himself by going out in the coutryside and perfecting* the art of painting. His poetic work often displays lines showing him having the eye of a painter, as we see in the middle of the verse. Not sure what effect though Elliott has in mind with the confusing phrase "thunder-whispering forest."

"Remarks Upon Elliott’s Poetry & Memoranda Of The Poet"

by Thomas Lister

This 26 page article by Lister appeared

in a book by January

Searle called “Memoirs of

Ebenezer Elliott, the Corn Law Rhymer, with

Criticisms upon his Writings.”

The book was published in 1852, three years

after Elliott died. January Searle was a pseudonym for G. S. Phillips,

a friend

of both Elliott and Lister.

Lister’s article began on page 215 of Searle‘s book. The

Barnsley poet started by describing how Elliott saw

scenery with the eye of a painter as they

rambled around the Dearne Valley. He

then described trips the two men made to Grimethorpe,

Thurnscoe, Sprotborough, Wath and Darfield. Poetry

with music was the next topic with particular reference to the poem

“Ribbledin,” an Elliott poem set in Sheffield’s

Rivelyn Valley. Lister then added a description of the Rivelyn

Valley by

the noted author and journalist William Howitt, owner of Howitt’s

Journal.

Lister went on to review several of Elliott’s poems especially

‘Etheline” which

Lister praised highly and revealed that the poem was stimulated by a

hike the

two friends made to Conisborough Castle. Both Elliott and Lister

thought highly

of “Etheline” which showed a lack of judgment from the pair since

critics were unimpressed

by the poem. Lister then commented briefly on Elliott as a public

speaker and

how his politics made him unpopular in some quarters.

The Appendix to Searle’s book

contains even more by Lister. Pages

183 to 199 are relevant now. We learn that the two poets lived only

seven miles

apart and that Lister was a frequent visitor to Elliott ‘s home. Searle

then

wrote a short sketch of Lister’s life and made a comment about “The Rustic

Wreath” – “Some of the poems are beautiful; and they are all

above mediocrity.

In character they are simple and descriptive, sometimes pathetic and

humorous.

The ‘Yorkshire Hirings’ is full of fun, and hits off the provincial

dialect in

admirable style. Since his duties commenced as post-master, Mr. L. has

written

no more poems.” Was that because he was too busy or did the official

status of postmaster

mean he was above writing verses? He retired as postmaster in 1870 when

he was sixty years old.

The next few pages of the Appendix (page 187 on) were used

to quote a very long letter from Lister headed: "Post

Office, Barnsley, 4th mo. 21st,

1850." In the letter, Lister lamented the death of his friend and

reminisced

about the life and work of the Corn Law Rhymer.

After the end of Lister's letter, Searle then used a two

page extract from "Mr. Lister’s

note-book for the year 1836."

In the extract, Lister revealed

that he had actually met Elliott earlier than 1837. They were

introduced by

Charles Pemberton, the famous Shakespearean actor and fiery orator.

This happened in

1836 or even the previous year. (In fact, Searle implied the two poets

met in 1835, and Pemberton is known to have visited Sheffield in 1834

and twice in 1835. So 1835 was the date Elliott and Lister first met

and not in 1837).

Lister then recounted his first visit to Elliott’s Hargate Hill home

and told of how

Elliott

bought the house. Lastly, Lister gave details of the two friends

climbing a

hill at Shirecliffe (now a district of Sheffield) where

Elliott had set “The Ranter,” the poem

that made the Corn Law Rhymer famous.

Barnsley

Library has a manuscript day book, mainly about birds & wildlife. Article

on Lister in “Sketches of Remarkable

People” by Spencer T. Hall who Lister had met before 1837. Obituaries

in Barnsley Chronicle

(31 Mar 1888 p8) and in Barnsley Independent (31 Mar 1888 p6). This is

not

meant to be a comprehensive nor an up-to-date summary of information on

Lister since

the the information was simply noted down around 2010 when I was

looking for information on Ebenezer Elliott. Consult Barnsley

Archives for details of more recent files archives@barnsley.gov.uk