Introduction

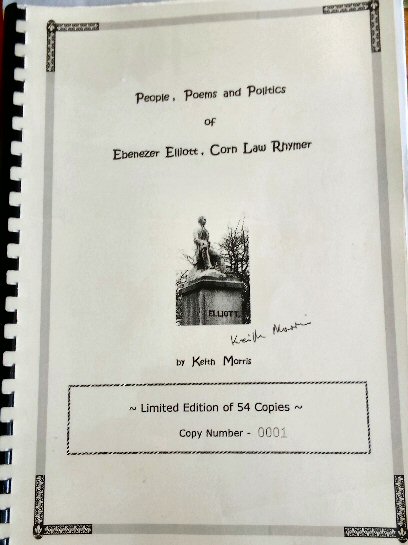

People, poems and politics of ebenezer Elliott, corn law rhymer

From

humble beginnings in

The

writer’s earlier book, “Ebenezer Elliott: Corn Law Rhymer and Poet of the

Poor,” was very much an introductory work, concentrating on the basic biography

with a survey of the Rhymer’s verse penned by Ray Hearne. “People, Poems and

Politics of Ebenezer Elliott, the Corn Law Rhymer” is a much different book; it

takes a deeper look at various elements in the poet’s story and makes a good

number of new discoveries about Elliott & his activities.

“People,

Poems and Politics of Ebenezer Elliott, the Corn Law Rhymer” does what you

might expect with such a title. It looks at the poet’s relationships with

several personalities who were important to the bard; it examines the famous

“Corn Law Rhymes,” it even discovers some unpublished poems by Elliott and it

probes his politics, particularly in the early years of the Chartist Movement

when the Corn Law Rhymer took a more central role on the national stage than had

been understood previously. Behind the title lie two further levels which make

the volume more useful to the serious reader. In the first place, the book is a

very good resource on Elliott since it includes the most detailed chronology

ever published of the poet’s life and work. Added to this are a useful reading

list and Elliott’s important Preface to the “Corn Law Rhymes.” The Preface has

only rarely been printed anywhere, yet it gives real insight into the poet’s

motivation at a critical point in his career. The Preface is fairly long (which

explains why the piece has not often seen publication) but it is worth a

careful read since Elliott’s truculent character inexorably takes centre stage.

The

book can also be viewed as a sort of biography since it begins with an

autobiographical fragment written in 1841. The fragment has been mined by every

commentator for biographical information, but the complete text, as printed in

this study of Elliott, has not appeared in any of the books written about the

poet. As the fragment deals only with the early years, it has been supplemented

by two further articles which help the reader to form a complete picture of the

Poet of the Poor. One is a major article which appeared in the

The

research findings described in this book show the poet in a different light to

earlier studies which perhaps judged Elliott too much by his poetry. Today we

are inclined to give greater weight to his other achievements, while still

appreciating his verse – though not all of it! Elliott called himself “the Bard

of Free Trade,” and it has been accepted for a long time that he was effective

in bringing an end to restrictive trade practices such as the Corn Laws. What

has been largely missed is that Elliott was not an influential member of

parliament, he was not a powerful landlord: he was a man of the people, an

ordinary man who cared enough to stand up and spout. At considerable risk. This

took great determination and courage for a man in his position.

In

another sense Elliott was a modern man well ahead of his time. His concern for

working conditions, his wish to improve himself and his fellow men are today

better appreciated. He was, despite what many people believed, a man of peace. “I

would not hurt a fly, not even if it stung me” he once remarked, and he styled

himself “the Bard of Universal Peace.” These beliefs are those of a character

who would not be misplaced in society today. The poet’s impressive concern for

the educational welfare of local working people is demonstrated through his

dedication to the Mechanics’ Institute as described in a section of this book.

This is another thoroughly modern attitude; so, too, is the bard’s struggle to

educate himself – something usually described today as Lifelong Learning.

Given

that Elliott was a dunce at school, it was a major achievement to become a

political leader & a celebrated poet who was even read in

Then let me write for

immortality

One honest song, uncramp’d by forms or

creeds,

That men unborn may read my times and me,

Taught by my living

words, when I shall cease to be.

His

“honest song” is worth studying for there are certainly quality poems in the

poet’s work. It is good news that a university professor is preparing a new

edition of Elliott’s poems for publication. This will help the revival of

interest in Elliott’s poems & in the political activity of a remarkable man

whose character was “uncramp’d by forms or creeds.”

Many

newly discovered letters by Elliott appear in this volume, including those he

wrote to Robert Southey and one he wrote to William Wordsworth. Also to be

found in the book are several letters written by James Montgomery, the

“People,

Poems and Politics of Ebenezer Elliott, the Corn Law Rhymer” details much new information

about the Poet of the Poor &

portrays him as a positive force in the cultural & political development of

Sheffield; in this sense it adjusts the balance in the poet’s favour after

years of neglect and negative commentaries.

Keith

Morris

Rotherham

2005

“Ebenezer

Elliott: Corn Law Rhymer & Poet of the Poor” (joint author with

Ray Hearne), Rotherwood Press 2002, ISBN 0 903666 95 2

“Wassop Worksop” published by the author, 2000.

“I Were A Worksop Lad” published by the author, 1998

“Pawnshop on Monday: Sheffield Folk Remember” (consultant editor), Hallamshire Press 1994

Click the Anvil to return to the Ebenezer Research Foundry