The Year of Seeds

Fifty Sonnets by Ebenezer Elliott

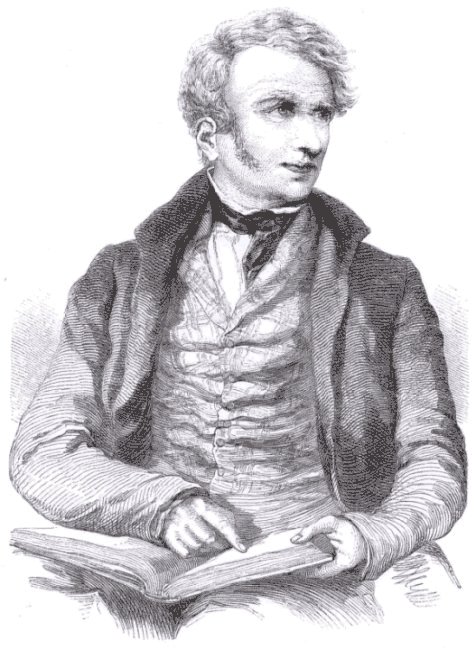

Ebenezer Elliott

in 1847, aged 66

A Sketch by Margaret Gillies

What is the meaning of the title?

The title is puzzling: what did the poet have in mind? The sonnets roughly follow the seasons through the year, but this just appears to be a loose framework - surely Elliott would have kept to 12 sonnets had he meant to mark each month? While the title could indicate a seedbed of ideas, this does not hold true. Nor is there a discernable sequence as only occasionally does a sonnet connect with the previous one. It does suggest that "The Year of Seeds" is a random collection of sonnets. However, the plight of the poor is often prominent in the sonnets as is usual in the work of the Poet of the Poor.

Willoughby Wood

"The Year of Seeds" is respectfully dedicated to R. Willoughby Wood who lived at Campsall near Doncaster and who was a keen foxhunter. In "The Year of Seeds" Elliott writes insultingly of hunters, so it is rather odd to see a dedication to a fox hunter. Wood's saving grace was that he was a pro-reformer who attended the meeting in Sheffield where Elliott introduced the Charter to local people. Elliott was prepared to overlook Wood's love of hunting since Wood was in favour of reform. Unusual for one of his well-to-do background.

At the end of the dedication, we read: [To Willoughby Wood Esq.] ... "I dedicate This Cycle Of Revolutionary Sonnets." An interesting statement.

An Exploration of the Sonnets

In Sonnet 1, Elliott takes up his revolutionary sonnets notion and quarrels with "the law of the sonnet kings" using Petrarch, Milton and Wordsworth to support his challenge to the sonnet rules declaring:-

For cheaper music, suited to my thoughts.

In Sonnets 6 & 7 a "willing" pauper dies, and Elliott mocks a "tax-fed Squire" for his shallow ideas. We see some wit here from the poet - very unusual - when he says that the Squire believes "That Prairie is the Book of Prayer." Shakespeare is mentioned in Sonnet 7. This is a surprising diversion, though a footnote claims that Shakespeare once acted in Sheffield. (Elliott lived in Sheffield until he retired).

Sonnets 10 & 11 complain that "kinglings" and "despotlings" are idle, treacherous and self-interested. Standard Elliott who always harangued the landed gentry for being high-handed tyrants.

With Sonnets 14 & 15 the year has progressed to May. The poet tells of a boy dying in a workhouse unattended by his family who had been driven to emigrate to Australia "Where the bad thrive best."

Sonnets 16 - 18 describe the memories recorded by churchyard gravestones. The local village poet should not be interred in a pauper's grave but in the village graveyard where his ancestors rest. So, here, less than halfway through the 50 sonnets, we note that Elliott has described a good number of tragic events.

With a sudden change of subjects, Sonnet 19 is mainly about Wordsworth.

Although the Rabble's Poet has moved to sunny June in Sonnet 21, he is not bright and cheerful since he looks despondently at more gravestones grumbling that "Oblivion is the doom of all." Somewhat surprisingly, the next sonnet switches to troubles abroad where the powerful agree "To ban the wretch who struggles to be free." Elliott showing an interest in lands abroad where the authorities oppress the poor, just like in England.

Sonnet 24 continues to consider gravestones and is quoted below as a good example of Elliott's work:-

For hours, or years, or age-long years of years,

On sand, clay, stone. Thus, chroniclers of tears

Die, but not soTime's History of Pain.

Rooted on graves, Truth bears a living flower!

Men may forgive, but wounds their scars retain

As warnings! and the Powers of Good ordain

That to forget shall not be in our power.

For worst ills, too, have roots: they are the fruit

Of plotted action worn to habitude;

And the grey dynasties of Force might live,

Safe in their privilege of fraud and feud,

If agony died recordless and mute,

And to forget were easy as forgive.

Kinder Scout is a plateau of peat bog high above Edale in the Peak District. Kinder's dramatic scenery is a big draw for hikers today as it was in Elliott's time. We know that the poet would take long walks from his Sheffield home into the Peak District - see for instance the article WinHill. In Sonnet 28, Elliott's love of freedom is inspired by Kinder Scout which makes the poet wish all men were free. The sonnet was dated March 5th 1848. Typical view of Kinder below.

We are not lonely, Kinderscout! I stand

Here, with thy sire, and gaze, with Him and thee,

On desolation. This is liberty!

I want no wing, to lift me from the land,

But look, soul-fetter'd, on the wild and grand.

Oh that the dungeon'd of the earth were free

As these fix'd rocks, whose summits bare command

Yon cloud to stay, and weep for Man, with me!

Is this, then, solitude? To feel our hearts

Lifted above the world, yet not above

The sympathies of brotherhood and love?

To grieve for him who from the right departs?

And strive, in spirit, with the martyr'd good?

"Is this to be alone?" Then, welcome solitude.

Sonnets 34 to 38 refer to international affairs in Sicily, Italy, Hungary and Moscow. Napoleon puts in an appearance too.

By contrast, Sonnet 39 turns to desolation and death - something which concerned the aging poet. The poem is bleak and powerful as shown below:-

And life a corpse laid out. The clouds had died

Of sunless cold. O'er all things snow was spread,

Mute as the billows of a frozen sea;

And, voiceless, the eternel wind swept wide

Under dumb skies, o'er steel-like sea and land.

Echo herself had perish'd, but reply

From her none needed was, where time forgot

The letters of his name, and sound was not,

And motion soundless; and all victory

Crown'd freezing Death, who, with world-covering hand,

And sword-like pen - and with an inward laugh -

On Mind's vast grave, wrote dead Hope's epitaph

In ice for ink: "Her Dream was Liberty."

Sonnets 45 & 46 tell of the end of the year ... and the end of life. Sonnets 47 & 48 pose questions about mankind's fear of death, reflecting Elliott's own worries. The final two sonnets dwell on the power of the Almighty, and thoughts that the bard would be remembered for "the sadness of my slander'd lays." An interesting comment.

After the final sonnet, Elliott resumes his ruminations about the sonnet form which we saw in the opening sonnet of "The Year Of Seeds." The bard then makes the following statement:- "After much theory, and some practice, I venture to propose the measure of this sonnet as a pattern to english sonnetteers; for while, to me, the Petrarchan, in our language, is, at once, immelodious and inharmonious, the music of this, in its linked unity, is both sweet and various, and when closed by an alexandrine, majestic."

While

considering the poet's views on the sonnet form, it is interesting to

view another short poem by Elliott called "Powers of the Sonnet."

Why

should the tiny harp be chained to themes

In

fourteen lines, with pedant rigour bound?

The

sonnet's might is mightier than it seems:

Witness

the bard of Eden lost and found,

Who

gave this lute a clarion's battle sound.

And

lo! another Milton calmly turns

His

eyes within, a light that ever burns,

Waiting

till Wordsworth's second peer be found!

Meantime,

Fitzadam's mournful music shows

That

the scorned sonnet's charm may yet endear

Some

long deep strain, or lay of well-tolled woes;

Such

as in Byron's couplet brings a tear

To

manly cheeks, or over his stanza throws

Rapture and grief, solemnity and fear.

In the last few years of his life, Elliott suffered much pain and misery from his poor health. Living off the beaten track, his activities and social contacts were quite limited leaving him time to spare for his poetry - when he felt in the mood. The result of this spare time was "The Year of Seeds." The fifty sonnets were an outpouring from the elderly poet in his declining years and display a surprising commitment to his art. A number of the sonnets are well written but some are inevitably vague and confusing, yet the references to the need to improve social conditions and the desire for liberty at home and abroad show that the bard was still up to date with the political concerns of his day. All in all, the sonnets present an odd picture but they do demonstrate Elliott's understanding of the sonnet form. Whether the sonnets can be described as "revolutionary", the reader will need to make up their own mind. The Athenaeum liked them announcing in 1850 that "The Year Of Seeds" contains many fine and nervous thoughts and beautiful images."