EBENEZER ELLIOTT

(1781 - 1849)

NEW POEMS (2)

More new poems from the Corn Law Rhymer

For

space reasons, these discoveries have been kept apart from those listed

in New Poems 1.

The Artizan's Holiday (1836)

The Starvation Valve (1836)

The Corn-Law Rhymer in the Country (1843)

Elegy On Eliza (1810)

Stanzas Spenserian (1835)

Inscriptions (1836)

A New Churchyard (1835)

The Wild Honeysuckle (1836)

To The Wood Anemone In A Day Of Clouds (1836)

Songs 1 (1836)

The Heroes of Cutlerdom (1832)

Hood Hill Hymn (1839)

England in 1844 (1844)

Song (no date found)

|

How like a tyrant in distress, Though late, at last bettray'd, This land appears in loveliness! What gloom of light and shade! Dark mirror of the darker storm, On which the cloud beholds his

form! Like night in day, how vast and

rude On all sides frowns the heath! This horror,- is it solitude? This silence, - is it death? Yes, here, in sable shroud

array'd, Nature, a giant corse, is laid. Is motion life? There rolls the

cloud, The ship of sea-like heaven; By hands unseen its canvas

bow'd, Its gloomy streamers riven. If sound is life, in accents

stern Here ever moans the restless

fern; The gaunt wind, like a spectre,

sails Along the foodless sky; And ever here the plover wails Hungrily, hungrily,; The lean snake starts before my

tread , The dead brash cranching o'er

his head. And on grey Snealsden's summit

lone, What gloom-clad terrors dwell! It is the tempest's granite

throne , |

The thunder's lofty hell! Hark! hark! – Again? – His

glance of ire Turneth the barren gloom to

fire. Now hurtles wild the torrent

force, In swift rage, at my side; The bleak crag, lowering o'er

his course, Scorns sullenly his pride , - Time’s eldest born! with naked

breast, And marble shield, and flinty

crest! And thou, at his eternal feet, To make the desert sport, Bloomst all alone , wild

woodbine sweet, Like modesty at court! Here! and alone, - sad doom, I

ween, To be of such a realm the queen. Far hence thy sister is – the

Rose, - That virgin-fancied flower; Nor almond here, nor lilac

blows, To form th' impassion'd bower. Nor may thy beauteos langour

rest Its pale cheek on the Lily's

breast. Who breathes thy sweets? Thou

bloom'st in vain , Where none thy charms may see; For, save some wretch, like

homeless Cain , What guest will visit thee? No leaf but thine is here to

bless; - How lovely is thy loveliness! |

Although this poem is listed as a new poem by the Rabble's Poet, it actually is a re-working of an earlier poem, namely On Seeing A Wild Honeysuckle In Flower Near The Source Of The River Don which Elliott composed in 1817. The 1817 version appeared in Peter Faultless To His Brother which was published in 1820. Lots of lines in the two versions are the same, though the 1836 version has 10 more lines. Verse 1 of the 1836 version appears as verse 2 of the 1817 version. After a gap of 19 years, the Corn Law Rhymer has re-visited the earlier poem, found it wanting and made some modifications before offering it to the New Monthly Magazine under a changed title. As noted elsewhere, Elliott was digging up juvenalia once he became an established poet. He hoped that his new found fame would encourage the magazine to publish earlier titles.

Where the poet mentions "grey Snealsden's summit," this refers to Snailsden Moor, not far from Dunford Bridge in the Peak District.

|

Broom glowed

in the valley For William

and Sally, The rose with

the rill was in tune; Love

fluttering their bosoms, As breeze s

the blossoms, They strayed

through the woodbines of June. Oft, oft he

caressed her, To his heart

press'd her, The rose with

the woodbine was twined; Her cheek on

his bosom, Like dew on

the blossom, Enchanted the

tale-telling wind. |

Poor Sally

was bonny; But Mary had

money, Aye, money

and beauty beside; And wilt thou,

sweet Mary, Thou fond and

unwary! Deprive the

wise fool of his bride? Yes;

bee-haunted valley! Poor

heart-broken Sally No more with

her William will stray; “He marries

another! I'm dying! –

Oh, mother, Take that

sweet woodbine away!”

|

Once again, the date for the publication of this poem is questionable. The subject and treatment suggest that the poem was written much earlier than 1836.

|

I saw a horrid thing of many

names And many shapes: some call’d it

wealth, some power, Some grandeur. From its heart

it shot

black flames That scorch’d the souls of

millions

hour by hour, And it’s proud eyes rain’d

everywhere

a shower Of hopeless life and helpless

misery; For, spous’d to fraud,

destruction

was Its dower! But the cold brightness could

not

hide from me The parent base of crime, the nurse of poverty! All-unmatch’d Shakespeare and

the

blind old man Of London, hymn in every land

and

clime Our country’s praise; while

many as

artisan Spins for her glory school-

taught

lays sublime, |

Oblivious spirits gently will

inter; But three unborrow’d strains

will to

all time Give honour, glory, highest

laud to

her – ”Thalaba!”

“Peter

Bell!” “The Ancient

Mariner!” The good and vile. Men, in

their

words and deeds, Live, when the hand and heart

in

earth are laid, For thoughts are things, and

written

thoughts are seeds, Our very dust buds forth in

flowers

or weeds. Then let me write for

immortality One honest song, uncramp'd by

forms

or creeds; That men unborn may read my

times and

me, Taught by my living words, when

I

shall cease to be. |

This

poem appeared in the New Monthly Magazine in March 1835. The last nine

lines of the poem were published in Elliott's Poetical Works under the

title "Spenserian," so at some stage the first two verses

have

been dismissed.

The Artizan's Holiday

Oh! blessed, when some holiday Brings townsmen to the moor, And in the sun-beams brighten up The sad looks ot the poor. The bee puts on his richest gold, And if that worker knew How hard, and for how little, they Their sunless task pursue! But from their souls the sense of wrong On dove-like pinions flies, And throned o'er all forgiveness sees His image in their eyes. Soon tired, the street-born lad lies down On marjoram and thyme, And through his grated fingers sees The falcon's flight sublime. Then his pale eyes, so bluey dull, Grow darkly blue with light, And his lips redden like the bloom O'er miles of mountain bright. |

The little lowly maiden-hair Turns up its happy face, And saith unto the poor man's heart, "Thou'rt welcome to this place." The infant river leapeth free, Amid the bracken tall, And cries, "For ever there is one Who reigneth over all:- And unto Him, as unto me, Thou art welcome to partake His gift of light, his gift of air, O'er mountain, glen, and lake. Our father loves us, want-worn man! And know thou this from me - The pride that makes thy pain his couch, May wake, to envy thee. Hard, hard to bear, are want and toil, As thy worn features tell; But wealth is armed with fortitudes, And bears thy sufferings well." |

This poem is another discovery by Diane Gascoyne, an Elliott

enthusiast. Diane found the verses in the Sheffield Iris newspaper for

12th January 1836. The Iris had reprinted the poem from the

Monthly

Repository Jan 1836. The Iris noted that "The Artizan's Holiday" was

from "Songs For The Bees," an unknown work by the Poet of the Poor.

Note that verse two introduces a bee to the action.

"The poor man" is revitalised by the power

of nature which flows from god & his love. The theme of the

tired worker being healed by nature is a theme often used by Elliott,

while his belief in the almighty occurs often enough too.

It is surprising to see a poem of this period by Elliott without a stirring message about free trade or the Corn Law. This lack of political statements makes the poem unusual.

|

|

"A power," he saith, "dwells westward hence, Between the sea and sky; His kindred are the winds and clouds, And things that swim and fly: He loves to feed on bonny men Where sea-snakes dive and swim; All man [xxxxxxx] a grave, like me - Send, send your men to him." Aye, send them to the dolphin's home, "In that perfidious bark,* Built in the eclipse of Britain's mind, And ring'd with curses dark:" Dupes! cherish still all beastly things, But throw your men away! The bonny men, the strong young men, With faces bright as day! |

Unfortunately verses 2 and 3 have words which were obscured by a Sheffield City Libraries rubber stamp. Hooligans!

Once

again, the poem was discovered by the researcher, Diane Gascoyne, who

found the poem in the Sheffield Iris newspaper for November 15th 1836.

Elliott quite often added notes to the end of his poem. He did so with

this one and the notes appear below:-

* We know what sort of ships those are in which the poor Irish go to that place where the wicked cease from troubling. But, thanks to the Cormorancy, their bread-tax is become a decree, now irreversible, that ultimately and soon the taxes shall be laid on land alone, unless four, or five, or six millions of human beings - in a few years, or months, it may be - will simultaneously consent to die, merely that some fifty thousand of the most ignorant and worthless of mankind may continue to live in hideous luxury. If they are Kings, was Charles the First a God? "See!" saith the scaffold. Yet, at this moment, trembling for privilege, (or is it prerogative?) they are devising means how best they may waste or destroy the most valuable and costly of all wealth, men! In the meantime, to statute scoundrelism, and beggary self-doomed, the plundered doff their hats! How then can warning reach the evil-doers? Villainy will become fate, and retribution overtake them unannounced. Why not? Can we believe in God, and believe that bread-tax eater will escape his vengeance? The thought is impious; it dethrones Justice.

| Oh Devon!

when thy daughter died, The primrose check'd the green hill's side, The winds were laid, the melted snow Was crystal in the river's flow, The elm disclosed its golden green, The hazel's crimson tuft was seen, The schoolboy sought the mossy lane To watch the building thrush again, And birds, upon their budding spray, Rejoiced in April's sweetest day; She, too, rejoiced, thy wondrous child, For in the arms of death she smiled! And when her wearied strength was spent; When pain's disastrous strife was o'er; When, palliid as a monument, Eliza moved not; spoke not more; Her prattling babes might deem she slept, And wonder why their father wept. Why wept he? If, with soul unmoved, From all who loved her, all she loved, From husband, children, she could part, And meet the blow that still'd her heart; Why wept he? Not that she was gone |

To

wait beneath th' eternal throne, And kiss in heaven, with holy joy, Her youngest born - that fatal boy! And smile, a brighter spirit there, On him, still doom'd to walk with care! Oh, still on him, from realms of light The seraph-matron bends her sight, Still, still his friend in trouble tried, Though sever'd from his lonely side! He weeps! for truth and beauty rest Beneath the shroud that wraps her breast: Taste mourns a sister on her bier, And more than genius claims a tear. The blessing of the sufferer Bedews the turf that covers her; And orphans who she taught to read, Drop over her a siver bead, Who did not pass in scorn your door, Ye children of the helpless poor! Oh, bless'd in life! in death how bless'd! - Her life in beauteous deeds array'd! Her death, serene as evening's shade! And bliss is her eternal rest! |

Under the title of the poem "Elegy On Eliza", Elliott has an interesting dedication: "Wife of Benjamin Flower, Of Cambridge, The Father Of The Liberal Newspaper Press."

Benjamin Flower (1755 - 1829) was a printer, a writer and a journalist. Like Elliott, Flower was an Unitarian but the latter had some unconventional views. He edited the liberal Cambridge Intelligencer newspaper which denounced the war with France. From 1807 to 1811, he was the owner of the Political Register newspaper. When in gaol for libel, he was visited by Eliza Gould, who was noted for her philanthropic work, and soon after Flower was released, the couple married. Eliza died in 1810, so the poem should have been written about this date; yet the poem only appeared in the New Monthly Magazine in 1836. There is a problem here. Further the publication of the poem in the New Monthly Magazine in 1836 was seven years after the death of Benjamin Flower. Elliott's dedication is not to the late Father of the Liberal Newspaper Press, so that is evidence that the poem was composed much earlier. The date 1810 seems appropriate. At this date, Elliott was 29 years old, was writing poetry and was in correspondence with Robert Southey, the famous poet and literary figure, who was making encouraging remarks about the Corn Law Rhymer. The poet did not achieve fame until the literary world discovered The Ranter in 1830. When Elliott was widely recognised as an important new voice, then the editor of the New Monthly Magazine would have begged the poet to submit more of his work for publication in the magazine. This is a good argument for explaining the long gap between the poem being written and the publication date of 1836* (*see next paragraph). In fact the magazine published 14 poems by Elliott in this year: which means that caution should be applied to any poems apparently published in 1836. For example, Elliott wrote a letter to the editor of the magazine on 11th August 1836 enclosing "a worthless cargo" of 13 new sonnets which he hoped might get published.

When Eliza Gould became Mrs Flower she gave birth to two daughters, Sarah and Eliza. This gives us two people called Eliza Flower, namely mother and daughter. This can cause confusion, and it may need emphasising that "Elegy On Eliza" was for the mother and not for the daughter! Eliza the daughter was born in 1803 and was to become a celebrated musician who composed the famous hymn "Nearer, My God, To Thee." She sent contributions to the Monthly Repository as did her father.

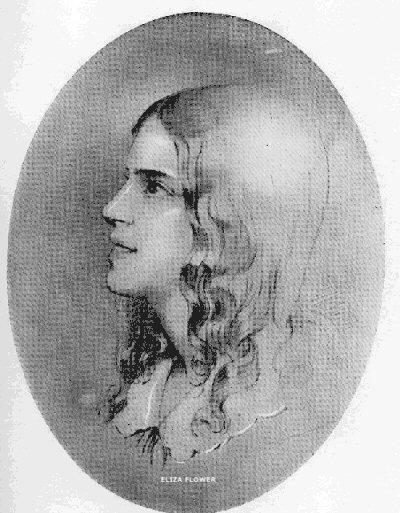

Eliza Flower, the daughter

The owner of the Monthly Repository was Rev Fox. For some interesting information on the relationship between Eliza Flower and Rev Fox and Elliott's contact with both, please see the article on this site about Fox & Flower. Elliott was in contact with Rev Fox and had about 30 poems published by the Monthly Repository. A letter from Elliott to Rev Fox (dated 11 Sept 1836) is in Rotherham Archives.

For Elliott to have written the "Elegy On Eliza" poem, it is obvious that the poet had very good connections with Benjamin Flower and his wife. The latest research shows that Flower was the publisher of Elliott's first poem, "The Vernal Walk" and also his second poem "The Soldier" published in 1810. More information on the publishing relationship is available.

New

research has

revealed that "Elegy On Eliza" appeared in Elliott's "Peter Faultless

To His Brother Simon" published in 1820. In this volume, the poem was

entitled "Elegy" and did not bear the dedication mentioned earlier. The

two versions are almost identical, with just the odd word being changed

and with 4 lines being omitted in the 1836 version. Elliott was being

underhand in submitting his poem to the New Monthly Magazine as a new

work when it had already been published. The same is true of another

poem

called "Ilderim." This also appeared in the Peter Faultless volume and

then was included in the New Monthly Magazine in 1836. Again, in the

later version a few alterations were made by the Corn Law Rhymer and

the original verse 1 was dropped

The Corn-Law Rhymer in the Country

This is a very long poem

which takes

the form of a letter to Francis Fisher, a very close friend of the Corn

Law Rymer. More information on Francis Fisher can be found here.

The poem was found by Keith Morris in the journal Tait's Edinburgh

Magazine for September 1843, pages 561-563. The work is addressed to

"his friend Francis Fisher." The length of the poem would reflect on

the high value 'the rabble's poet' placed on his friendship with

Fisher.

In 1843, Elliott had been living in his country retreat for two years,

long enough to be bored by his isolation, to miss his friends &

to long for good company.

Dear

Francis, - 'Twas on All-Fools' day, Their

horses, on the common bare, Neighing,

"Come, come," to my black mare; While

she, in plenty to the knee, Still

answered, "Nay, come you to me," When,

by my parlour fire, I read, In

Hunter's book, (his best, 'tis said,) Not

precepts wise about new tillage, But

stories old about "our village," And

that huge hall, whence Strafford bore His

third good wife, in days of yore. Discord,

a saint to churchmen dear, Dropp'd,

in those days, an apple here: Sir

Edward Rodis took up the apple, And

built, to vex the church, a chapel: Ah,

little dream'd he or his mate, That

priests would preach at Houghton Great, In

house of his, for church and state! And

much I fear, mankind will never Be,

as they should be, good and clever, Till

two curs'd plagues are hounded out, Call'd

He-Knows-many, and He-Knows-nought; For

He-Knows-wrong is sly and strong; While

He-Knows-might is dull, though stout: Sad

deeds are done by He-Knows-wrong! But

when came good from He-Knows-nought? No.

We must wait till He-Knows-right Shall

slay them both, in Christian fight, Ere

humble truth can be forgiv'n, And

earth rejoice - a humble heav'n. Meantime,

let's peel Saint Discord's apple, And

talk of preachers, and our chapel. One

of our pastors - we have two - (Of

course not sprung from Discord's apple,) Is

evangelically true, Elect

of God to serve our chapel. Who

preach'd above Sir Edward's nose; Bidding

us fly to good from evil, Chiefly

because we fear the devil. At

Darfield* stands his Church in-Co, Near

which a river windeth slow Beneath

the tower, time-tinged and strong, Whose

famous clock, which ne'er goes wrong, Hath

too respectable a chime To

follow vulgar railway time. That

chime of chimes no chime excels; Who

hath not heard of Darfield bells! Of

Darfield's prophet-preacher too The

evangelically true! He

is of "saintship old" a sample! Good

Francis, follow his example; And

don't get lick'd by worse than Turks For

preaching moral worth and works. No,

let the dread of hell defend Your

flock from sin, ray erring friend! Placed,

as they are, above the pit, On

a mere crust, which covers it! If

that crust break - why, down they'll go, Down

to the flaming lake below: This

you from sacred writ can show. Yet

you may hint, (perhaps 'twere fit,) That

if, unmarried, they have heirs, Or

fail, when scared, to say their prayers, They'll

each be burnt into a brick! To

build an oven for Old Nick, In

which he'll bake his brimstone pies! Garnish'd

with fried Socinians' eyes! But

I forget - I'm bearing hard on The

singers in our little chapel - Were

they, too, rais'd from Discord's apple This

a Yankee might boldly say, Nor

could my conscience answer, Nay. They

sing too long, and yet too fast, Each

driving to be heard the last. But

discords sometimes harmonize; And

one fam'd fiddle well supplies, By

sundry sorts of strange crack'd noises, The

want of modulated voices: Singers

and preacher well agree, They

to mend tunes, and sinners he When

will you visit our old chapel, To

see what springs from Discord's apple! And

hear them sing, and him exhort, Hoping

they've got a patent for't. Note.

Don't you tell all this, or hoot it, Now,

Francis, pull a prudish face, |

I know He loves and pities

vie: Therefore, in woman's smile, I seek Him ; in true hearts His goodness sec, In every deed that helps the weak, In every look that lessens pain, And bids the old feel young again; And still, when kindness speaks, I hear The footsteps of the Blessed near. But falsehood in the heart and eye, Like manacles on mind or limb, Degrades the Lord of Liberty - Backs the hymn'd of seraphim; And oh, when lours from man's proud brow Darkness,

which makes God's image tremble, Wine,

(a glass,) if home-made wine, Thanks

to the air of Argott-Hill**, I

wak'd - the beauteous vision fled; Much

have I sinn'd in deed and word, But

He to crush His child forbore; He

tells us not that we have err'd, But

bids us learn to err no more. I

care not who, in coat or gown, Wears

crop or wig at church or chapel, Converts

a village, or the town. And

throws, or gathers, Discord's apple; But

can I sage or Christian find In

men whose zeal misleads the blind? Assists

bad strength! and shuts the door, The

heart - against the victim - poor! No.

Who reviled Him crucified? The

servants of our meanest pride. Who

fed the hungry? He, who cried, "Feed

ye my little ones!" and died. You,

Francis, well-resolved, prepare His

cross profaned to lift and bear! You

on God's altar pure will lay No

hands impure; and good men say, Just

pleaders are themselves a plea; He

hears such preachers when they pray. Pray,

then, Beginner! - not for me; Nor

for God's doom'd, who sow, for gain, Woes

steep'd in crime, (such prayers were vain) But

for Man's doom'd! And who are they? The

famish'd slaves, whom laws betray; Who

mutely pine in sternest need; Whom

none salute, and many meet; Who

ask (unheard!) the fiends we feed - "For

leave to toil," that they may eat, And

rise up men - from Satan's feet. He

is the Christian, he alone, Whose

love is wisdom, (sad, when groan Millions,

but angel-glad to trace Heaven's

peace on earth's afflicted face) Teaching

the sons of toil and care To

earn sufficient, and to spare? Have

we no Christian teachers then! The

Corn-law Rhymer. |

*

Darfield was the

nearest village of any size to Elliott's home out in the wilds.

** Elliott's retirement home was on Hargate Hill, a short distance from

the hamlet of Great Houghton.

| Stop

here, Seducer! stop awhile! A villain's victim sleeps below. She drank the poison of a smile, And found that lawless love is woe. Too true to doubt the lip that lied! Too trusting maid! too fond to fear! Too oft they met on Rother's side; For she was young, and he was dear. Known by the arrow in her breast, She mourn'd her bonds, then join'd the free; Now Mary's sorrows are at rest, And her sad story speaks to thee. |

Although this short verse appeared in the New Monthly Magazine in 1836, it could well have been written much earlier. The line "Too oft they met on Rother's side" refers to the River Rotherham. Elliott left Rotherham to live in Sheffield in 1819, which would suggest the poem was an early one written while the poet was still living in Rotherham.

To The Wood Anemone In A Day Of Clouds

|

|

Why art thou

sad like me, Blush

cheek’d Anemone? Say, did the

fragrant night breeze rudely kiss Thy drooping

forehead fair, And press thy

dewy hair, With amorous

touch, embracing all amiss? And,

therefore, floweret meek, Glow on thy

vexed cheek Hues, less to

shame, than angry scorn, allied, Yet lovely,

as the bloom Of evening,

on the tomb Of one who

injured lived, and slander’d died? Or didst thou

fondly meet His soft lip

Hybla-sweet? |

|

And,

therefore, doth the cold and loveless cloud Thy wanton

kissing chide? And, therefore,

wouldst thou hide Thy burning

blush,

thy cheek so sweetly bow’d? Or while the

daisy slept, Say, hast

thou waked and wept, Because thy

lord, the lord of love and light, Hath left thy

pensive smile? What western

charms beguile The fair-hair’d

youth, forth from whose eyelids bright Are cast o’er

night’s deep sky, Her gems that

flame on high! That husband,

whose warm glance thy soul reveres, No floweret

of the west Detains on harlot breast; The envious cloud withholds him from thy tears. |

The above poem probably dates from 1836 when it appeared in the New Monthly Magazine, though it may have been written earlier and submitted to the magazine on a wave of popularity which happened to the poet after the reviews of the Corn Law Rhymes.

|

O'er breezy oaks – who’s sires

were Giants then When Charles in battle met “the

man of men” From Shirecliffe's crest I gaze

on earth and sky, And things whose beauty doth

not wane and die,- Rivers, that tread their

everlasting way, Chaunting the wintry hymn or summer lay, That brings the tempest’s

accents from afar, Or breathes of woodbines, where

no woodbines are. What earth-born meteor, in the

freshening breeze Burns, while day fades o’er

Wadsley's cottages? Upon the Hill beneath me I

behold A golden steeple and fields of

gold, That starts out of the earth

with sudden power, A bright flame, glowing

heavenward, like a flower, Where erst nor temple stood,

nor holy psalm Rose by the mountains in the

day of calm. |

Thither, perchance, will

plighted lovers hie; Then, when loud grief hath

sobb'd her long farewell, Laid o'er that dust, perchance,

a stone will tell The old, old tale, that breaks

the reader’s heart With its unutter'd words, which

cry “Depart!” And Time, with pinions stolen

from the dove, Will sweep away the epitaph of

love. Yet deem not that affection can

expire, Though earth itself shall melt

in seas of fire; For truth hath written on the

stars above, “Affection cannot die, if God

is love.” When'er I pass a grave, with

moss o'ergrown, Love seems to rest upon the

silent stone, Above the wreck of sublunary

things, Like a tired angel, sleeping on

his wings. |

This poem is an interesting one, as several of the lines appear in another Elliott poem called Lines (On Seeing Unexpectedly A New Church, While Walking, On The Sabbath, In Old-Park Wood, Near Sheffield). Very likely, A New Churchyard is an earlier working of the Lines poem. In line 2 of A New Churchyard, we see the name Charles without an explanation about who he represents. In the Lines poem, we get a solution to the mystery person in line 4; namely Pemberton. A footnote later identifies Pemberton as "The unequalled lecturer of the drama." Charles Pemberton (1790-1840) was a colourful friend of Elliott who walked with the poet around Loxley, Shirecliffe, Wadsley & Rivilin - areas of Sheffield not too far from the bard's Upperthorpe home. For more information on Pemberton, see the article on this site on Friends and Contacts of the Corn Law Rhymer

|

Here’s a health to our friends of Reform! And, hey, for the town of the cloud, That gather’d her brows, like the frown of

the storm, And blasted the base and the proud! Drink, first, to that friend of the right, That champion of freedom and man, Our

heart-broken Milton, who, rous’d to the fight, Again took his place in the van.* Then, to Palfreyman, Parker, and Ward, And Bailey, a star at mid-day; And Badger

the lawyer, and Brettell the bard, And Phillips, in battle grown grey; And Knight, whom the poor know and love, For he does not scorn to know them; And Dixon, whom conscience and prudence

approve; And Smith, though unpolish’d, a gem. |

And Bramhall, by bigots unhung; And Holland, the fearless and pure; And Bramley, and Barker, the wise and the

young, And Bentley, the Rotherham Brewer. Here’s a health to the friends of Reform, The champions of freedom and Man, The pilots who weather'd and scatter’d the

storm, The heroes who fought in the van! And since Russel’s bolus is driv’n Down the throats of Cant, Plunder, and Co. May the firm of the maggots take wing to that

heav’n Whither all the Saint Castlereaghs go! Or, while, like the bat and the owl, For darkness invaded they grieve, May the angels seize each Tory body or soul, Which the devil would blush to receive! *Northampton

|

This poem was written in 1832 at the height of celebrations for the passing of the Reform Bill. The poem was found in the Sheffield Courant newspaper. It praises the Sheffield men who were prominent in the campaign for reform of parliament. The poem was meant to be sung to the tune "Here's a health to them that's awa." The title of the poem reflects the cutlery industry for which Sheffield was noted. For more background to the politics in Sheffield at this time see the article on the Sheffield Political Union on this site.

O Lord our God Arise,

Scatter our enemies,

And make them fall;

Confound their politics,

Frustrate their knavish tricks,

On thee our hopes we fix,

God save us all.

On

22 Sept 1839 there was a large Chartist protest meeting on Hood

Hill near Wentwoth in South Yorkshire. Chartists came from Sheffield,

Barnsley and Rotherham to take part in the meeting. The Corn Law

Rhymer composed the hymn specially for the meeting and the hymn was

sung at the meeting which was described as a large demonstration.

Hood Hill is near the village of Harley and is close to

the large Wentworth estate near Rotherham, the estate was the onetime home of Earl Fitzwilliam.

Hood Hill is about 10 miles from Great Houghton where Elliott was living.

Earl Fitzwilliam and a group of friends were nearby but kept themselves separate from the protesters. His estate workers were in danger of dismissal if they were recognised.

1839

was a tough time for Elliott - he left the Chartist Movement which was

advocating violence and he left the Sheffield Working Men's Society.

His future son-in-law, John Watkins, was arrested for sedition. Elliott

also stood bail for Peter Foden who was also arrested for sedition. So

clearly times were interesting!

|

ENGLAND IN 1844

Lazy big Beggardom, Playing the fool! Helping with less and less Fast-growing wretchedness! Catch’d Cayley creakingly, Young England sneakingly Shearing calves’ wool! Capital profitless, - Doing what? Can’t you guess Eating his teeth! Married life, dog and cat: Palac’d thieves, scar’d and fat; Sorrow and verity Sobbing, “Prosperity Dead, lies beneath.” ***************** Young Wodehouse crustily, Crying dear wares; Want, with his tongue of fire, Seen o’er the famine spire! Richmond to hawk his fish, Knatchbull to beg a dish, Damn’d – And who cares? Bread-taxers stealing rates; John, thinking Church and State’s Hell is broke loose! Brassface and Timberface Half-fac’d by Doubleface! Foul things, with mouth and “legs,” Scolding o’er broken eggs! Killing the goose! Rushbrooke and Sotheron, Kept loonies, duller none, Not telling lies! Benett’s slaves full of cheer, “Except when bread is dear!” Benett, to keep it dear, Talking of cheaper beer – Juice, and no pies! |

Famine their battle-blade, Man against man array’d, Struggling for doom! Starv’d Erin’s Catholic Mining in Bishoprick! Brimless hat lacking crown, Slaving the Saxon down, Till the end come! Cobden, “our Man of men,” Doing the work of ten, Each worth a score; Bright, in the lion’s den, Champion of honest men, Lion and dove of peace, Hampden of love and peace, Worth fifty more. Gunpowder quenching flame; Jesus a hated name, Stanley sublime as Thom; Government Peeping Tom; Hunger, the only power! Scowling round town and tower, Darker than Death! Peel, hardest task'd of all! Gagg’d, kick’d, and mask’d for all, Cooking his hash! Slander’d man, wily man, Bare back, and empty pan, Gloomily waiting all For the great general – General Crash! Trade on her dying bed:

Lifting her languid head, Smiles, with sad brow: Land-leeches, damning us, Cry, “She was bamming us!” Farmers, in luck again, Trying to duck again, Milk a dead cow! |

SONG

|

Others march in Freedom’s van; Can’st not thou what others can? Thou a Briton! -

though a man! What

are worms if human thou? Wilt thou, deaf to hiss and groan, Breed white slaves for every zone? Make yon robber feed his own, Then

proclaim thyself a man. Still shall paltry tyrants tell Freemen when to buy and sell? Spurn the coward thought to hell! Tell

the miscreants what they are. |

Dost thou cringe that fiends may scowl? Wast thou born without a soul? Spaniels feed, are whipped, and howl – Spaniel!

thou art starved and whipped. Wilt thou still feed palaced knaves? Shall thy sons be traitors' slaves? Shall they sleep in workhouse graves? Shall

they toil for parish pay? Wherefore didst thou woo and wed? Why a bride was Mary led? Shall she, dying, curse thy bed? Tyrants!

tyrants! no, by Heaven! |

This

poem was found in the biograpy of Elliott written by John Watkins,

chartist, playwrite and son-in-law to Elliott. The poem has not

appeared anywhere else, as far as I know. The rhythm of the poem

reminds of "The Black Hole of Calcutta" and may date from this

time (1830/1). Elliott liked to use this question and answer format

which helps the rhythm trip along. The poem seems to demand people to

be self confident and challenge what is wrong with the present social

order. The phrase "palaced knaves" often occurs in the bard's poems but

what were the "Spaniel" references about? And who was Mary?

To

return to Ebenezer Research Foundry, please strike the anvil

?>